Like many young girls, I was crazy about horses. While I played with “Barbies,” my imaginative storylines cast them as competent horsewomen instead of fashion models, and I ditched all of the silly little high heels that came with them in favor of improvised riding boots. I collected models of horses, constantly drew pictures of horses, wrote stories, poems and songs about them, and loved the “Trixie Belden” book series, mainly because the title character was into horses! I welcomed any and all opportunities to ride, and didn’t lose interest even after I once found myself in the center of a rosebush when a friend’s pony decided that I was an unwelcomed passenger.

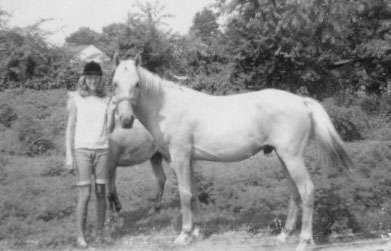

When I was in the 6th grade, a dream came true: I got a beautiful Palomino gelding that I named “Morning Sun.” He was gentle, yet spirited–the perfect match for a twelve year old girl–and he soon became my best friend. While “Sunny” and I sometimes went to horse shows, I especially enjoyed riding him on mountain trails, or on the farm behind our house. I spent countless hours just hanging out with him, brushing his golden coat, braiding his mane and telling him all about the trials and tribulations of adolescence.

One evening in the spring of 1971 when I was riding him, I slipped my hands beneath his mane and felt something unusual near his withers. On the right side where his neck joined his back, there was a swelling of some sort. When it didn’t go away, my parents called the vet.

I was fourteen at the time, and the thought that there could be something seriously wrong with Sunny never entered my mind. But the vet determined that it was a malady known as “fistula of the withers,” (also called “fistulous withers”) and said that he would have to operate to allow the large, destructive abscess to drain. While rare, a fistula sometimes forms as a result of a bad bruise, but we never knew how Sunny had been injured.

We took him to a local equine hospital for the surgery, and I waited outside while they operated on him. I’d never been the type to faint, but I came very close to doing just that when they brought him out. A large incision had been made high on his right shoulder near the ridge of his neck, and blood and pus-filled fluid had spilled all the way down to his right hoof.

When we brought him home, we were instructed to flush the area out twice a day with hydrogen peroxide and to pack the incision with gauze. The first night that my dad and I did this, it took 3 feet of gauze to fill the cavity in his neck….

And so a new routine began: twice a day we would squirt peroxide into the incision, wash off the burning drainage, pack sterile gauze deep inside of the wound, and give him an antibiotic injection. Although this procedure must have been painful for him, never once did he try to bite, kick, or avoid us. Instead, he’d simply look at us with his large, liquid brown eyes, accept the “twitch” that we used to keep him immobile, and let us do what needed to be done. (A twitch, by the way, is a loop of rope attached to a wooden handle. The horse’s upper lip is pulled through the loop, and then the handle is twisted, thus twisting the lip inside of the loop. While it doesn’t necessarily hurt, it serves as a distraction from other uncomfortable procedures, and most horses will stand still once the twitch is in place.)

Days passed into weeks, and there was no sign that any healing was taking place. The vets consulted with specialists in neighboring states, and no one had any answers regarding how to best cure this ailment or to hurry up the healing process.

Our family vacation that year was canceled in order to care for Sunny, and we kept him in his stall most of that summer to try to minimize the irritation of flies. I spent a lot of time out there with him, even rigging up an oscillating fan high on the ceiling to try to keep him as comfortable as possible. When he’d hear me approaching, he’d nicker a low greeting, knowing that he’d be rewarded with a carrot or a few apple slices.

At some point that summer, I clipped a small section of his mane and bound it with a rubber band and a ribbon. I’ve saved it all these years–it’s still in my jewelry box–as a reminder of how close we were that summer….

When the vets said they didn’t know anything else to try, my parents and I drove up through the Shenandoah Valley, stopping at Mennonite farms, seeking advice. As the Old Order Mennonites there still used horses to pull their buggies and plows, we hoped that they might know something about horses that the vets didn’t. Even though we tried some of their suggestions, nothing worked. The outer incision started to close a little, but the burning drainage continued to flow, and there was a distinctive dip forming along the ridge of his neck, indicating that tissue was being eaten away.

By fall or early winter we stopped using the gauze, though the rest of our routine continued, with some modifications–when you do something enough times, you figure out the most efficient way to get the job done. One cold winter night as I was holding him (as usual), my dad squirted the peroxide into the cavity and placed his hand over the incision to let the pressure build up. We’d found that this caused the drainage to spew out with force, and then we could wash a greater quantity of it away at one time. But that night as my dad removed his hand, the pressure-propelled drainage hit me directly in the face. As I ran gagging and crying to the house, I realized that Sunny wasn’t getting any better–and that he wasn’t going to get any better.

I still helped my dad with Sunny’s care–some of the time–but I was starting to “distance” myself, because the thought of what surely was to come was too much to bear. I was still grieving over the loss of my dog to cancer a couple of years before, and I didn’t feel that I could face the loss of my horse, too….

I knew that the vets had already advised my dad to “put him down,” but up until that night I felt that all he needed was a little more time to heal. It didn’t take an expert, however, to see that the dip in the ridge of his neck was becoming more and more noticeable, and as I washed the drainage and peroxide and tears from my face that night, I knew that the abscess was relentlessly continuing its course of destruction.

It was shortly after this that my dad attended a meeting of the Universal Youth Corps which was under the direction of his friend, Dr. George Ritchie, author of the book “Return from Tomorrow.” Dr. Ritchie, who was living in Charlottesville, Virginia at that time, was an area psychiatrist and a near-death survivor. What he experienced during the nine minutes that he was “dead” changed his life, and the Universal Youth Corps was a spiritual group that he started for teenaged boys, as a way to share his “knowings” about God and about our purpose in life.

At the close of the meeting, Ritchie asked one of the boys to offer a prayer, reminding him that “where two or more are gathered in the name of Jesus, He is there.” The boy, being aware of Sunny’s condition, said “God, please heal our friend’s horse.” My dad appreciated the boy’s concern, and thought it was a nice gesture. Dr. Ritchie, however, came over to my dad after the prayer, and said that while the boy was praying, he’d been told that if my dad gave thanks for the horse’s healing, he would be well in two weeks.

My dad didn’t tell me about this–he knew I was trying to separate myself from Sunny–but nonetheless he did give thanks each day for a healing that, quite frankly, seemed impossible to imagine after all of this time.

On the thirteenth night after the meeting, my dad was treating Sunny, alone, at 10 pm, and without thinking of the prayer or about Dr. Ritchie’s words, he thought to himself, “This horse is no better now than he was six months ago….”

The next morning, Palm Sunday, 1972, my dad headed out to the stable with his kit of medicine, syringes, and peroxide, and as he got closer, he didn’t see any drainage. Examining Sunny more closely, there was no sign of swelling, and he couldn’t even see the incision; sometime during that night, a miraculous healing had occurred!

I remember my dad rushing into the house, waking me up, telling me to come to the stable. He excitedly told me what had happened at the meeting, about the message that Ritchie had received, and about the promise that had been made. I just stared in disbelief at Sunny, and at the clean stretch of shoulder that had been covered with drainage for over ten months.

Did I cry? I don’t remember. Did I doubt it and question, and try to convince myself that it was nothing more than an incredible (and probably temporary) episode of coincidence? Yes, I did. I was fifteen years old, and I was scared to believe that Sunny had been healed in this way, and at the same time, I was scared to not believe it.

You can go to church and read the Bible, sing the familiar hymns and recite the prayers, but when something “impossible” happens–something that falls into the realm of the miraculous–your mind and heart need to “stretch” in order to absorb the full impact of what has occurred. The God of my childhood had changed over night, and the stretching that took place–as I adjusted to these changes–was both wonderful and very frightening.

As I grappled with doubt and belief and the evidence–parting the hair on my horse’s neck to try to even find the closed incision–I totally understood both awe and fear, on a very deep and personal level….

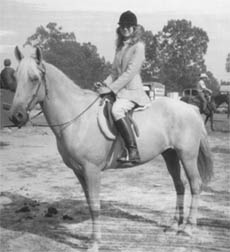

When the vets examined Sunny–the horse that they had advised us to put down–they had no explanations for his healing. But pronouncing him sound, I rode him for the first time in nearly a year a few days later, on Good Friday. Later, I resumed trail riding, entered him in shows again, and generally used him as any other healthy horse would be used.

When I went to college in 1975, Sunny went too; I was able to board him on a farm close to my dorm. After graduation I moved to an apartment to be closer to my work, and I made the decision to give Sunny to one of my friends from high school who lived on a small farm. Her husband had a Palomino, and it just seemed fitting that Sunny would live on “Golden Horse Farm” where he would have other horses for company and people who would ride him more often than I could. It was hard to say goodbye, but I knew he would be happy there, and it was good to know that I could visit and ride him if I wanted.

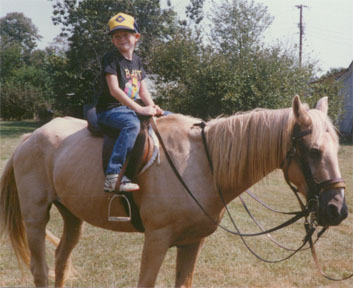

In the fall of 1991, my young sons had the opportunity to ride this very old and gentle horse when we visited my friend’s farm. As I looked into his tired but still beautiful brown eyes, stroked his mane and let my hand rest in the dip in his neck–the only lasting sign of his ordeal–I thought of the summer when he was truly my closest and dearest friend.

The miracle that saved my horse’s life certainly changed my life, because this event, like no other, moved me beyond a need to believe in God.

If that sounds strange, consider this: the word “belief” implies a choice that one makes to “believe” or to not “believe” in something. As I discovered when I was fifteen, “belief” is no longer necessary–nor an option–once you know, first hand, the power and reality of the force that we call “God.”

Books by Dr. George Ritchie on Amazon© SKB 2000, 2023

I love this story of, well, love. Unconditional and full of faith. I’m so happy you had many more wonderful years with Sunny. What a blessing!