A maternal colony of approximately 20 female Big Brown bats used to roost in the louvers of my attic each spring and summer to have and raise their babies. I first got involved in “bat rescue” in June 2005 when I found an unfortunate baby that had fallen from the louvers. I didn’t know much about bats at that time–and I certainly had some of the same “fear” or trepidation about them that most people do. But since I was presented with a tiny little baby that would surely die if I didn’t try to help, I got involved and I didn’t look back.

I learned quite a bit about these amazing creatures after my first “rescue” in 2005, and I also began to realize their importance in our environment. With White Nose Syndrome wiping out bats by the millions, each little colony of bats–and each little individual within a colony–is vitally important.

In trying to care for and protect the bats who lived in my louvers, I relied heavily on the knowledge and assistance of a local wildlife rehabilitator who specialized in bats. I also took a couple of classes on wildlife care and management through The Wildlife Center of Virginia. At one point I hoped to pursue my wildlife rehabilitator permit, but I was glad that I could at least help by being a rescuer and transporter.

Some years I didn’t find any fallen babies (which was a very good thing), but the Spring of 2011 was most unusual. Beginning in late May 2011, a record number of babies dropped out of the louvers.

I found Baby Bat #1 on May 25, 2011. It was the tiniest one I’d ever found, and it still had the dried thread of its umbilical cord attached to its belly.

We hoped the mom would retrieve it, but despite putting it out on the mesh on the side of the house for two nights, it was unclaimed. It was taken to the wildlife rehabilitator on May 28th.

****************************************************************************************

There aren’t any pictures of Baby Bat #2 because s/he was a success story! It was found at night and it appeared to be strong and healthy. It was also a little larger than #1. It was put onto the mesh as soon as it was found, and there was a lot of activity among the mother bats once I came inside. Within 30-40 minutes it had been retrieved! If only all of them could be that lucky!

****************************************************************************************

Baby Bat #3 was found on May 28, 2011. Aside from the coloration being different (Baby #1 and Baby #2 were more of a uniform charcoal gray), it also had a more “outgoing” personality.

When I’d find these tiny babies, they were usually dehydrated and very weak. A few drops of Pedialyte from a small, clean paintbrush often meant the difference between life and death.

I gave #3’s mother two nights to try to retrieve it by putting it on the mesh I had mounted on the side of my house below the louvers.

I took some more pictures of it when I brought it inside late that night. I held it upright, but they really prefer to be upside down!

Please note that most pictures of baby bats on each post on my site were taken in low light to avoid stressing them any more than necessary. The pictures were brightened and sharpened in Photoshop to better show detail.

They have 5 long toes on each back foot, and their wings are incredibly delicate.

Unfortunately, Bat Baby #3 was apparently orphaned, too, so it was taken to the wildlife rehabilitator on May 30, 2011.

****************************************************************************************

I found Baby #4 around 8:30 am on the morning of May 30, 2011. It was very weak and fully exposed in the sunlight. I’m surprised that I found it before a hungry Bluejay or crow did! I called the rehabber and asked what to do. Of course the best thing possible would be for its mom to get it, so I said that I’d put it out that night. It was so very tiny…

Unfortunately, it wasn’t picked up, either, so I made yet another 30-mile round trip to the wildlife rehabilitator’s farm on June 1, 2011….

****************************************************************************************

Why weren’t these babies retrieved by their moms? Big Brown bats are good mothers. They usually give birth to just one or sometimes two babies in the spring, and they can live to be nearly 20 years old in the wild. By contrast, most mammals of similar size give birth to multiple babies and can have multiple litters each year. Mice, for example, can have 40-60 babies in a year and have a life expectancy of about one year!

Bats belong to the order Chiroptera, a name of Greek origin meaning “hand-wing,” and they are more closely related to primates than they are to rodents! They’re the only true flying mammal. While it’s possible for Big Brown bats to become airborne from the ground, they usually need to swoop down from a height of at least a few feet in order to fly. Once in the air, however, they are remarkably agile and they can reach speeds up to 40 miles per hour.

Most species of bats navigate by means of echolocation, as do whales and dolphins. The biosonar they use for hunting is in a frequency range that humans cannot hear. In addition to the loud peeping sound that babies make, adults communicate with their young and with each other in a range that is audible to human ears. I’ve described the adults’ communication vocalizations as a raspy “electronic” sound, and some nights the chatter of the adults and babies in the louvers was quite loud!

While Big Brown bats usually don’t carry their babies with them when they’re foraging for food (and a nursing mother needs to eat her body weight in insects each night!) they can and do retrieve them if they drop from the roost–as was the case with Baby #2. So why didn’t the moms come for the other ones?

The most common predators of bats are owls. I’d heard an owl calling in the distance on the night of May 30, 2011 and I had to wonder if it had been attacking the mothers of these babies each evening.

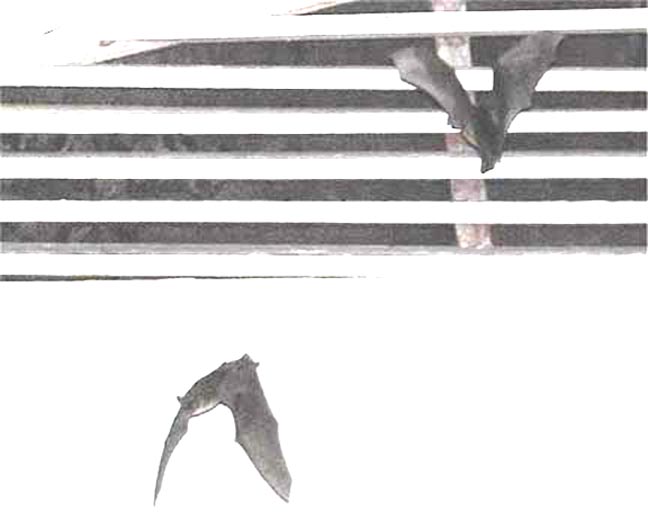

When I was taking Baby #4 off the mesh to bring it back inside, the adults were very active. I could see that the colony had moved to the north end of the louvers, away from the ladder which was leaning against the house on the south end of the louvers. You have to look closely, but in the intentionally over-exposed image below you can see something (bats!) between the slats of the louvers, left of center. I quickly snapped some pictures, capturing a few adults in flight, but my presence was obviously disturbing to them.

No babies fell that night. No babies fell the next night, either, and when I was out watering the garden around 9:30 pm on June 1st, there were no bats flying overhead, which was quite unusual. I then realized that I couldn’t hear the normal chatter of mothers and babies in the louvers. They were gone. ALL of them!

The colony returned to the louvers about a week later, and I found Baby # 5 on June 8th.

****************************************************************************************

Baby #5 was older than the others I’d found previously, but that made sense as the colony had been gone (somewhere!) for about a week. This one was clinging to the concrete foundation of my house, low to the ground. Remembering the successful retrieval of #2, I immediately put it on the mesh, but since it was so weak and dehydrated, it wasn’t peeping. I mixed up some Pedialyte and climbed up the ladder to give it a drink there instead of bringing it inside. It was a very warm, humid night so I left it outside a little longer than I’d left the other ones.

When I checked on it a couple of hours later, it had climbed to the top of the mesh–beyond my reach. Not good. When I went back outside, it wasn’t on the mesh and I hoped it had been picked up–or maybe it had successfully flown!–but instead I found it on the ground. I brought it in and heated up some goat’s milk for it.

I accidentally spilled a few drops of milk on the cloth I was using to hold and support this little bat–a girl–and she started sucking on the cloth. So cute. ❤

I took a quick video of her trying to get all of the goat’s milk; she was hungry!

When I called Robin, the wildlife rehabilitator, on the morning of June 9th to let her know I’d found another baby, all she said at first was, “Oh, no….” She then said that she was starting to wonder if the moms “knew” something, and instead of these babies being orphaned, maybe the moms were purposely rejecting them for some reason!

With a sigh, she shared the sad news that the other three I’d taken to her had died. They’d all seemed to thrive at first, but then one by one they started into a decline that she couldn’t stop–and she had raised countless baby bats over the years.

Baby #5 appeared to be strong and healthy, so we hoped she’d have a better chance of surviving than the younger and weaker babies did. (And she did.)

Bats are such amazing creatures–so sensitively and superbly designed for the natural world. We hoped that the Big Brown bat babies of 2011 were not the “bellwether” indicators of the negative effects of electromagnetic frequencies, radioactive contamination (from the Fukushima disaster earlier that year), and other toxic pollutants that are an ongoing threat to our environment.

**************************************************************************************

As I say on each of the “bat pages,” I was caring for these baby Big Brown bats with the support of a licensed wildlife rehabilitator. As a safety-conscious rescuer and temporary caregiver, I can help keep a young or injured wild animal warm and hydrated, but turning it over to a wildlife specialist gives it the best possible chance of surviving and someday returning to its natural habitat, where it belongs.

**************************************************************************************

There is so much misinformation, superstition and fear about bats. One long-standing myth is that “all bats” are rabid. Not true! Less than one-half of one percent of bats contract rabies, but that said, it is important to remember that any frightened or injured wild animal can bite! For that reason, no bat should be handled with bare hands. Wildlife rehabilitators who plan to work with rabies vector species must receive a series of pre-exposure rabies vaccinations before they can be licensed.

I think that our cultural view of bats has been largely shaped by frightening images of “Dracula” and Halloween. By contrast, in China bats are seen as symbols of happiness, longevity and good luck!

The unfortunate bat in a house–scared witless and usually being chased by a frantic human armed with a tennis racket or broom–is certainly going to look and sound as fierce as it possibly can. Additionally, most pictures of bats show them in a defensive posture, and that has only served to perpetuate the very negative and scary image that people have of them.

Bats are mammals, meaning that the babies are born alive and suckle milk from their mothers. On average, female bats give birth to just one baby per year, and they can live for 20 years! They are more closely related to primates than they are to rodents, and they are not blind. Many species of bats are in danger of extinction due to White Nose Syndrome, loss of habitat, and accidental or intentional eradication and extermination due to human fear and ignorance.